Tuesday 24 February 2015

Blindspot - "A Night At The Opera" and "The Navigator"

I remember a Saturday evening many years ago sitting down with my Dad to watch the Marx Brothers. I think we had tuned into PBS around 7PM and a double bill of Monkey Business and Horse Feathers was showing. Together they didn't even total 2 and a half hours, but holy crap did we cram in the laughs. It was silly, goofy and appealed to every juvenile instinct I had in my body (and still have). It seemed to have the same effect on my Dad since he sat in his chair giggling in that "Dad" fashion and shaking half the house along with him. Of course, that just made everything that much funnier. I was probably about 10-11, so I was also old enough to catch some of the puns, banter and sharpness of these obviously practised comedians and realized that this was a craft. A well-honed one.

And speaking of artists and their crafts...Buster Keaton remains to this day one of my all-time favourite artists in any medium. Far more than just simple slapstick, his silent comedies of the mid-to-late 20s were things of beauty and marvels to behold that would make you smile, laugh and question basic laws of physics. A somewhat "life changing" experience was watching a 3 hour American Masters program on PBS dedicated to Keaton (which I fortunately taped to VHS and wore down to microscopic width). His life had tragedy, regret and failure, but also contained some of the greatest work to ever be caught on celluloid. As the "great stone face", Keaton rarely broke a smile or showed a sense of fear while throwing himself (or mostly being thrown) info a myriad of dangerous stunts and physical gags. Though he was also an obviously well-rehearsed funny man with razor sharp timing, the falls, leaps and tumbles seemed almost improvised. It was part of his brilliance and was fascinating to hear him reflect on the broken bones and sets of cat-lives that he had. Those interview clips of Keaton in his late 50s also greatly reminded me of my Dad - there was just a certain way he told a story.

While watching these two films, it was fun to contrast what the Marx Brothers and Keaton each took from the rich comedic environment of vaudeville. Though they both retained the manic energy of stage comedy, they displayed it in different ways. As mentioned, Keaton focused it almost entirely on his sight gags that occasionally felt like dares gone wrong, but demanded a Cirque Du Soleil performer's strength, agility and finely tuned sense of balance (not to mention massive pain tolerance). As an example, an old clip from an early Fatty Arbuckle short shows him resting a foot on a counter while he tries to unstick his other foot from the floor. When he successfully peels it from the gooey molasses he had spilled, he lifts it up onto the counter WHILE THE OTHER FOOT REMAINS THERE. He appears to hang there in mid-air for far longer than any self-respecting pull of gravity would allow and then falls into a heap on the floor. It's remarkable, surprising and very funny.

The Marx Brothers, though still pretty good with a pratfall themselves, funnel most of their creative juices into the more verbal, musical and clownish elements of vaudeville. Groucho was given most of the good lines and putdowns (of anyone within his line of sight), but he also typically had several wonderful bits of verbal jousting with Chico as they each layered spoonerisms on top of assumptions and formed perfect moments of miscommunication. Each film also regularly had outlets for their music - Groucho's catchy songs, Chico's playful, wiggling-finger piano playing and Harpo's mostly delicate harp solos. Regardless of the plot, the lovers they were trying to help put together and the selfish schemes they were trying to torpedo, they never forgot to show the joy of just clowning around for the simple sake of amusing oneself (and hopefully others around them). To call them boisterous would be like calling a dozen, coca-cola-caffeinated 9 year-old boys playing video games a quiet play date.

Both films are somewhat similar in that they each have very distinctive moments and scenes that help define classic comedy from the early days of Hollywood, but also - when viewed as entire films - fall somewhere around "average" on a grading scale. A Night At The Opera contains the wild and ridiculous cabin scene that stacks people on top of each other before they spill out to the hallway and provides all of the aforementioned antics (including both Chico and Harpo doodling on a piano in front of very amused children), but sputters in several sections and offers little humour from any plot points. Well, OK, Chico and Harpo playing catch in the orchestra pit of the opera is still damn funny...

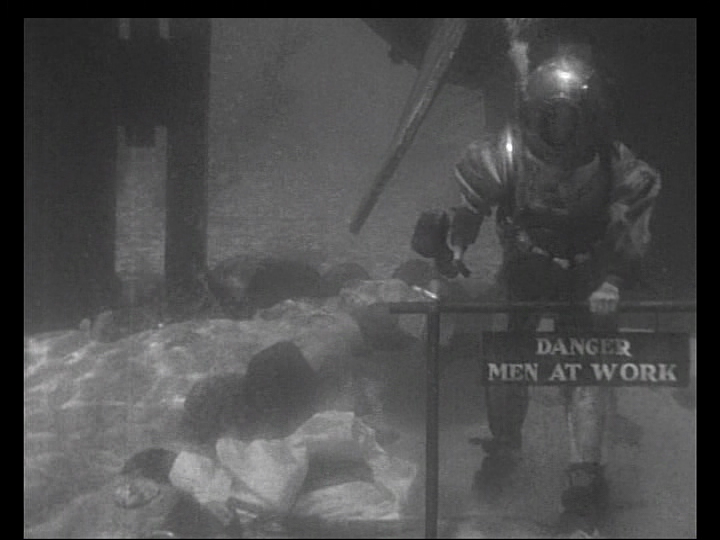

Keaton's The Navigator contains an underwater sequence that - especially for its day - is quite impressive. With a bulky diving suit on, Keaton is filmed using a lobster as a pair of scissors, fencing with a swordfish and fighting off an octopus. There's also some inventive and silly humour in the kitchen and a variety of Buster's slips and bumblings, but the dominant scenes are around an encounter with dark-skinned cannibal savages. They want to board the abandoned ship on which Keaton and his potential girlfriend have been stranded, but not much funny happens during these extended scenes and they seem to only serve two purposes: 1) reminding the "savages" of their inferiority and 2) allowing a good final gag to save them. At 58 minutes, it's pretty breezy, but even so it slogs a bit once they reach that island.

Nevertheless, both films do provide ample evidence of their classic style of humour while also keeping audiences reasonably entertained. I'll be seeing my parents this coming weekend as they prepare for an upcoming move, so I'm thinking I might bring along a sampling of both artists' films. At 87, my Dad is much less willing to go along with an anarchic bunch of maladroits or catch the subtlety of the deft contortions of a silent comedian, but I'm pretty sure the Marxes or Keaton can still get a good couple of chair shakes from him....

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)