Motifs in Cinema is a discourse across 22 film blogs, assessing the way in which various thematic elements have been used in the 2012 cinematic landscape. How does a common theme vary in use from a comedy to a drama? Are filmmakers working from a similar canvas when they assess the issue of death or the dynamics of revenge? Like most things, a film begins with an idea - Motifs in Cinema assesses how the use of a common theme across various films changes when utilized by different artists.

I'll be honest - I had mixed feelings when Andrew (of Encore's World of Film & TV) asked me to participate in this blog-a-thon about motifs and themes found in the films of 2012. I was excited to hear that numerous different bloggers (including several Toronto friends) would be giving their own perspectives on pervasive themes, but I worried about my own participation - I'm not one to usually look for overarching thematic content across different films as I rarely see it as a concerted effort by those filmmakers to go after those topics in the same calendar year. However, Andrew's idea afforded me a few angles. First of all, we were asked to compare and contrast the approach of different movies to a specific theme. Secondly, we could actually choose from a provided list, so I had some say in what I might be examining.

The parenting angle had already been chosen by a couple of other bloggers (Andrew was kind enough to offer it up to me, but I didn't want to have anyone shift their strategies), so I chose another one that I'm becoming much more acquainted with every day: Aging. I've never been one to overly worry about getting older, but the last couple of years have brought that whole concept a bit more to the fore. Partially because of my own creaking bones and minor health issues, but primarily due to my Dad having struggled through some major health issues. He's doing much better these days, but 2011 certainly brought a whole crapload of perspective to what it means to grow old. I'm not sure I was ready for it all, but there it was. Given that, I didn't want to solely focus on the tail end of the aging process, so I thought I would take a look at a variety of films from 2012 that covered a wide spectrum of the stages of life.

Childhood

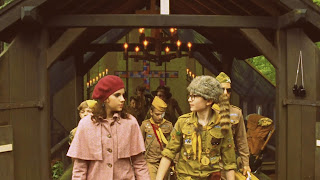

Moonrise Kingdom - apart from being my favourite film of the year and yet another great example of Wes Anderson's style, aesthetic and amalgamation of his own themes - is a wonderful portrayal of what it can be like to be a kid. It's not just its adventurous aspects or how it handles a first brush with love blooming, but also the depiction of how as a child you sometimes feel you already have all the answers and are much more mature than you might get credit for being. In fact, you feel you may be even more mature than any of the adults around you. If it doesn't necessarily give you an accurate picture of what it's like to be a child who looks at life differently than his/her peers, it provides you with a window into what it might feel like to think you have it all figured out. Both kids have confidence in their actions and words, confidence in each other and not much use for what they perceive to be the limiting rules of their elders.

Contrast this with The Odd Life Of Timothy Green - a movie that similarly has its central child (despite having a great deal of naivety) filled with a calm sense of confidence and things to teach the adults around him. It dabbles in the fantastic upon our introduction to Timothy - a boy who seemingly was willed to existence by his parents, but appears to have but a short time to impart some lessons to the adults and townspeople around him - but then struggles to ground its story in a realistic setting. It stays afloat as a movie mostly on the charm of its titular character as played by CJ Adams, but it stumbles with how it depicts Timothy's childhood experience. Part of his lesson is to show his parents that kids are resilient and come what may will survive and persevere. He does this by never letting anything affect him - no matter what happens, Timothy retains his confidence and a smile on his face. By attempting to place the story and characters in the real world, it just doesn't feel like an honest look at how a child manages to navigate the pitfalls they encounter. In this case, Anderson's tactic of creating a separate universe within which his characters live allows for a much truer representation of what it feels like to be a kid.

Teenage Years

Part of being a teenager is that desire to get to adulthood. You can almost feel the desperation to get to that next level of responsibility so that you can make your own choices. Not only do you feel like you know everything, you know that you know everything. Hence rebellion. Brave, Pixar's first attempt at building a story around a female protagonist, lives in this space during its first half. Princess Merida wants to pursue her passions, but Mom is restrictive and insists she tend to her duties. This sets up the best relationship of the film and what is essentially its core - a mother and daughter who fight and struggle for control while also sharing a great deal of commonalities and strength. The movie wasn't universally loved - in particular due to what many perceive as "run of the mill" stuff intruding into the story in its second half - but that relationship alone was enough for me (I enjoyed the rest of it too).

Michel Gondry's experiment The We And The I took a different approach to examining the rebellious and eager to flex their adult muscles teenagers. Parents, for example, are nowhere to be seen. The entirety of the story (except for some flashback and fantasy scenes) takes place on a city bus bringing a large group of teens home from their last day of high school. If you can get past the utterly unlikable aspects of many of these kids (and a dearth of acting talent in some cases), the film delivers a wide variety of intersecting relationships, attitudes and energy. The mid-section of the film pops with so much exuberance, spirit and vigour that you can't help but feel like a teenager yourself at times. It's not a matter of relating to these kids or even liking them (I mean come on - they're teenagers!), but a case of planting you in their shoes and creating a vortex of activity whirling about you to give you that feeling you might occasionally recall from your younger, chest-thumping days.

Perks Of Being A Wallflower also mostly dismisses the parental influence, but it wholeheartedly embraces the peer one. As a parent myself, it became pretty clear even in the early days of elementary school that children typically garner a great deal of their attitudes, self-worth and ideas from their own peer group - much moreso than their parents (I'm not saying parents have no part - just that they get pushed aside in many cases once the child reaches school). Perks Of Being A Wallflower was not only one of the more affecting films I saw last year, but it also does an excellent job of putting you in the character's shoes - in this case, those that belong to an adolescent boy who hasn't found any grounding yet. He can't relate to anyone, doesn't get the feedback he needs and always feels on the outside. One of the benefits of that, though, is that he meets a group of kids who also know what it's like to be on the outside looking in. They embrace him, pull him into their own group and become his support. Growing up is too hard to do alone.

Gaining Maturity

You could easily slide 21 Jump Street into a discussion of the Teenage Years since the majority of the story takes place with its two undercover officers mingling in a high school environment. Due to a mix-up and an altered landscape at the school, they essentially switch roles: the geek becomes popular and the stud is shunned. It would be a stretch to say that they fully mature after reliving their school days, but seeing things from another perspective and getting several second chances does bring them a few steps closer to adulthood.

The man-child finally growing up was "explored" in several comedies throughout the year. The best (and most subtle) was Sleepwalk With Me which has its central young male adult struggle through trying to figure out why his life seems to be stalled in both career and relationship. Part of his maturation is to accept where things have gone wrong, take some chances and stop waiting for things to happen. In Ted, John's life is also somewhat stuck, but he's happy to keep it there (seriously, if you've somehow managed to get Mila Kunis as your girlfriend, you really shouldn't be rocking the boat). His best buddy Ted is essentially symbolic of his carefree youth that he doesn't want to let go. Though the story is pretty predictable and the conflicts arise when and how you expect, it did manage in the midst of its crudeness to show the character's growth in awareness. It even managed some charm. Jeff Who Lives At Home looked at two brothers also stuck in neutral - one in typical living-in-my-parents-basement style while the other takes much for granted and is in denial of the issues in his relationship. After spending some time together and numerous mishaps, they finally start making some headway on the process of accepting responsibility (which was seriously overdue).

A different take on growing into adulthood came from Olivier Assayas' Something In The Air. Essentially a look back at his own youth, it's a wonderful example of those times when you still needed to fully figure out your convictions. Though it captures its era and politics as well as you possibly can, the movie really is about this young man's progression from idealist to someone more pragmatic and capable of seeing the grey in complex situations. In other words, he matures.

Parenthood

It would figure that the least successful movies of the bunch would be those aimed directly at my own situation - the middle-aged adult wrestling with getting old and raising kids. Though I usually find enough to like in any Judd Apatow movie, This Is 40 is easily his most frustrating. I thought there was a great deal of potential for Apatow to make not only a funny film, but an insightful one about reaching success (home, family, job) and having things fall apart in different ways. Though he did manage to provide several solid moments between the couple, he failed to create truly sympathetic likable characters. You have to want these people to overcome each new crisis, but at some point I pretty much gave up caring about them. They aren't nasty people, but each time they shot themselves in the foot they just became more and more irritating.

Even worse, though, was Friends With Kids. With its abysmal tag line of "Love. Happiness. Kids. Pick two." and only-in-the-movies premise of two platonic friends deciding to have a child together, the film borders on insulting numerous times. Granted, I'm taking it a bit personal, but the canard that kids ruin a happy marriage is not only reductive but it isn't overly interesting. There's little to no subtlety in the examination of how kids affect your life (don't get me wrong - things do change) nor any thoughtful discussion. And some of these characters are quite nasty people.

Even with extraordinarily reduced expectations, if you expect anything perceptive out of What To Expect When You're Expecting, then I expect you will be sadly disappointed. Sure it has a few entertaining moments (mostly due to what individual actors brought to tepid material), but it has nothing to contribute. At all.

Reflection

A pair of sci-fi time travel movies provided their older characters a chance to reflect on their past. Looper brings both the old and young versions of its main character Joe together with opportunity for the former to right some wrongs. Though the old version of Joe acts in ways that may appear quite selfish, he's in fact being very selfless - everything he does is for the sake of another person. Young Joe has little concept of this, but old Joe has learned a thing or two in his time. Why the film works exceptionally well for me is that young Joe actually discovers how to be selfless as well. It was a capability he had all along, but he just didn't know it.

Men In Black 3 isn't quite as successful, but works far better than you might imagine. A great deal of that is because of Josh Brolin's fantastic performance as a young Tommy Lee Jones (he wasn't mimicking, he was inhabiting...), but the framework of the movie (as goofy and forced as it is sometimes) allows us to see Agent K's earlier life and helps us appreciate how he became who he is in the present day. K's gruffness and crankiness makes sense now.

Decline

Aging necessitates slowing down due to the physical breakdown of the body through natural processes, but also due to choices you've made in the past. Skyfall, though it nicely sets itself up at the end to continue the adventures of James Bond for a good long while, gives us one of the hardest working Bonds we've seen thus far, but this time with real consequences to his body and health. Sure he can still bed the beauty, but everything doesn't come quite as easy as it used to for James. He bruises, scars, gets tired and is moving a step or so slower than in his salad days - not what we've typically come to see from this super-est of agents.

An even greater demonstration of a single person's decline into old age is presented in the only documentary in this set: Beware Of Mr. Baker. Archive footage shows how Ginger Baker was capable of performing inhuman drumming feats while in Cream and a variety of other projects, so it's sad to see the morphine-addicted shell he's become. But he's brought most of it on himself - his lifestyle, his rash decisions and his selfish nature have led to the brutish, angry man he is.

The Golden Years?

Which leads us to the old folks...I didn't see either The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel or Hope Springs, so I can't discuss how apparently wonderful it is to get old. If you ask Clint Eastwood's character in Trouble With The Curve, I'm pretty sure he'd sneer and bark at you to get out of his face. Or possibly punch you out. He hates being old and is still somewhat in denial. He continues to do his job using his old tried and true methods - even when he physically can't do things as well (in particular, his sight is failing him). Whether you admit it to yourself or not, the physical wear and tear on your body that aging causes is going to happen - so it's a matter of what you do with that knowledge and how you accept it. Trouble With The Curve makes that its central message, but it does so in rather obvious and occasionally cornball ways. Director Robert Lorenz has collaborated with Eastwood a great deal over the last decade and it doesn't look like they wanted to try anything new or challenging with this film. So they stuck with tried and true and delivered a rather pedestrian affair.

Amour is anything but pedestrian. It has a simple message - you'll get old, you'll die and it'll be horrible - but instead of telling you, it punches you in the face with it. It's immediately effective and you feel worn out by its end as you watch good people slog through the coda of their lives, but for me it didn't leave any lasting bruises. The octogenarian actors of the film are incredible, but short of its message I had little to take away from Haneke's latest. I totally understand and respect the approach he took with it (were more movies this straightforward...), but it didn't stick and was never as affecting as I thought it should have been.

So what did I learn about the aging process in 2012? Well, it's a helluva ride with bumps and obstacles galore. And it's worth every broken down hair follicle and wrinkle.

Saturday, 16 February 2013

Monday, 11 February 2013

Blind Spot - "The Reckless Moment" & "This Gun For Hire"

I haven't been on a Film Noir bender in awhile and it's damn well due. So for my opening salvo in the 2013 Blind Spots, I grabbed a pair of Noirs that I not only felt I should have seen by now, but that I just simply wanted to see right now. I expect from a more mainstream perspective, these two films weren't exactly gaping holes in my cinematic knowledge, but I've been yearning (yes, I said yearning) to see them both. The additional push is that The Reckless Moment is directed by Max Ophuls and he's a director that I'd like to dig into this year. My only experience with him is the lovely Letter From An Unknown Woman and I've cobbled together 3 or 4 of his films on the PVR (oh TCM...you give and you give...), so I'm keen to see more of that constantly moving camera of his. By the way, both of these movies were watched via the PVR, but my capture card is providing horrible resolution on Windows 7 so I've borrowed these screenshots from other sites...

Once Noir gets a hold of you, it's hard to shake. Like an addictive drug, Noir just leads to more Noir. I'm overstating of course, but Noir's ever-present feeling of doom, its creeping hand of fate and its shafts of light painted with purpose across every inch of the frame lures me in every single time. Even the "lesser" Noirs manage to ensnare me. Not that every Noir is the same, but they share certain characteristics of style tone and theme. Indeed, both The Reckless Moment from 1949 and the earlier by 7 years This Gun For Hire share stylistic touches as well as central male characters who float through their dark lives. Both of these men end up glimpsing some possible redemption through the eyes of a woman (these ladies are not your typical femme fatales even though they may be the "cause" of the male's downfall) as they accept the fate they always knew was approaching.

Ophuls' The Reckless Moment is easily the stronger overall picture - in craft, consistency and storytelling it shows a greater command of filmmaking. Even though it has a very melodramatic style with a highly arched main performance by the lovely Joan Bennett, it still manages to sneak in many subtle aspects of Noir such as shadows that creep into the house or stair banisters that suddenly feel like they're jail cell bars. Bennett plays a housewife named Lucia whose husband is away from home for long stretches due to work (after having been away for several years with the army) and even though she's doing just fine thank you very much, you're given the feeling that she's on the verge of breaking down and needs her man back at her side ("There's nothing wrong that Tom's coming home won't cure"). This goes doubly so whenever she deals with her fractious 17 year-old daughter Bea. She tries the strict and stern route to match with her harsh looking glasses, but it's just an open invitation to an already rebellious teenager to do exactly what she doesn't want her to do. For example, despite her warnings, Bea meets up with a seedy older man named Darby in the family's boathouse one night (Lucia had tried convincing Darby to leave her daughter alone, but that too failed). After displaying his true colours to Bea, an argument ensues followed by a tussle, a whack on the head and a tumble off the balcony. Bea runs off and the next morning Lucia finds him on the beach dead (always be careful of poorly stored anchors). She goes into protective mode and covers things up as best she can, but it's never that easy is it? Initially the story has you wondering if she has made the situation worse by covering it up and focuses on whether she'll get away with it or perhaps take the blame for it herself. Has her over-protective style put the family in jeopardy? I worried a bit initially that it might turn into a cautionary tale about happens when a woman tries to be strong and take charge of her family (as many women were now engaged in the workforce post-war), but fortunately Lucia's strong determination put those fears to rest. However, she soon has more than just the police to worry about as a man named Donnelly (James Mason) drops on her doorstep. He's in possession of some letters that Bea wrote to Darby (initially held as collateral for a debt Darby had) that appear to now hold a higher value due to their potential to cast suspicion on Bea. Mason conveys a message from his boss that "We want to liquidate our stock while the market is high", so now Lucia is forced to consider paying for the return of the letters to keep away any additional police snooping.

In comparison, This Gun For Hire gives off a straight ahead B-movie vibe. It starts off with a strong portrait of the titular character - a hired killer who is gentle with stray cats, but has little feeling for the people around him. He's been given his assignment details, carries out the task with a small wry smile on his face and even dispassionately dispatches his victim's "secretary" who wasn't supposed to be there ("they said he would be alone"). It's an effective scene with tension built through her unexpected presence, a kettle's whistle and a young girl who sees the killer while playing on the stairs. Alan Ladd is almost too handsome to play this killer named Raven, but he pulls the loner hired gun off quite well. One notable scene has him answer his contact's meek question "how do you feel when you do...this?" (pointing to a newspaper headline about the killing) with a short to the point "I feel fine". But after that sharp beginning, there's a let down as the story sets itself up. There's simply nothing overly special to indicate it will dazzle with its style or its substance - unless, that is, you count the presence of Veronica Lake. She was born to dazzle. It's not just her gorgeous looks or that trademark swooping hairstyle, but her voice is just tailor-made for Noir. Unfortunately, her pipes aren't given much of a workout on her less-than-snappy dialogue. However, she is given a chance to sing (or rather, lip-sync) as she warbles through a couple of tunes while doing magic acts at a club. Both performances are terribly cheesy - one of them including goldfish and a fishing rod - but Lake confidently works her way through them. And no one has ever looked as good wearing a fisherman's hat. The club is owned by Gates, the man who most recently hired Raven, and he's involved in a complicated scheme to steal chemical secrets and sell them to enemies of the state (in this case Japan - they would use the poison in bombs to deliver "Japanese breakfast food for America"). Lake's character Ellen is asked to do some undercover work while she works at Gates' club (the government suspects him) and being a good old fashioned American girl, she agrees to help out her country. Meanwhile her detective boyfriend is looking into the recent double murder while Gates is trying to double cross Raven. But a coincidental meeting between Ellen and Raven on a train leads Gates to believe they are in cahoots. Along with stirring the plot's pot, the scene on the train provides another example of Ellen's kindness as she offers Raven a dollar even after she catches him stealing $5 from her purse. It plants an early seed with Raven that perhaps not all of humanity is rotten.

The plot of This Gun For Hire has too many coincidences and stalls somewhat, but it's still mostly an entertaining ride (if only for this early 40's gem of a line directed at Ellen from her boyfriend: "Oh Sugar, what does it take to get you to darn my socks, cook my corned beef and cabbage and confine your magic to one place and one customer?"). It's not until its final half hour, though, that the Noir style really starts to make more of an impact - a thundering one in fact as it kicks off with a lighting strike. It's almost like that bolt has scared the movie awake as it jitters and jumps its way through the shadows and winds its way from the dark rooms of a mansion to a refinery and a sewer system. Raven and Ellen are chased as flashlights slash across the screen and it dawns on him that the woman he is dragging around is the only person that has stayed true to him (she didn't rat him out to the cops). He watches her tend to him as he did to his cat and he allows himself to be convinced to mend his ways...In The Reckless Moment, Lucia has a similar effect on Donnelly. He too works for a ruthless boss and has developed an uncaring view of the state of the world, but Lucia starts to have an effect on him. He's obviously smitten (Joan Bennett is perhaps less immediately sensual than Lake, but no less beautiful) and tells her "I never even did a decent thing in all my life. I never even wanted to until you came along". The story has more fun with its plot elements by shifting where the tension lies: Will she get away with the cover-up? Will she or Bea become suspects? Will Donnelly's boss come after the money? Now that an innocent person is involved, will she try to save them? Though you can sense where the fates will have a hand in the ending, you're never sure how they will get there due to the different paths the story navigates. In a similar fashion, Ophuls' camera is equally restless as it follows people up and down staircases (spinning around them as they climb or hovering on their shoulder as they descend), tracks them along the street or barges in through a window. Along with timely uses of shadowplay and some scenes of overlapping dialogue (Scorsese and Altman must have been acolytes), the film very effectively uses all these stylistic touches to keep the nerves a bit more frayed throughout.

Both films use an anti-femme fatale to help their longtime male criminals find some redemption after having given up on humanity. In both cases, of course, there is a cost. Each of the criminals is quiet, a loner and very intelligent (Raven improvises numerous times while Donnelly tries out several plans to help Lucia), but fate dealt them a bad hand early on and has come for its due. The films certainly depart a bit from each other with their approaches to story and style, but the Noir characteristics are prevalent and help reinforce the doomed nature of both men. Max Ophuls' stamp is imprinted far more deeply upon The Reckless Moment than the one by unsung Frank Tuttle on This Gun For Hire, but both use their conventions wisely and create mood and tension (This Gun For Hire just decides to save a lot of it up until its conclusion). If neither may ever crack the pantheon of film, watching both back to back has most definitely whetted my appetite for more Noir. Is there a cure for that? Yes, and it's more Noir.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)